Subscribe to the podcast via: iTunes | RSS Feed | Email Newsletter

Some people who watched the entirety of ECW will argue that 1996 was Paul Heyman's creative peak. Some wouldn't, also, but it's a line I've heard enough to explore. See, 1996 was arguably the year (up until this point) where ECW achieved the greatest gains with the least resources, but how it compared to the previous couple of years is an interesting point of debate. 1994, a year where ECW's product improved by an immeasurable distance. 1995, where the improvement was fair shallower but the balance of compelling storylines and world class talent was, for a promotion of it's size, incredible. But with WCW hoovering up much of the "imported" talent as the battle for ratings on Monday Night's heated up, the question remained in 1996 whether ECW could follow its best 12 months with a group of unarguably less talented performers.

It wasn't quite that cut and dry at the turn of the year, while Malenko, Benoit and Guerrero had long since gone the Mexican contingent of Paul Heyman's contact book was still very much accessible, something which he'd run for as long as he could as winter became spring before the likes of Rey Mysterio Jr, Juventud Guerrera and even Konnan (given the unenviable task of getting something, ANYTHING, out of Sandman) formally departed for WCW.

They were beaten to the break by the Public Enemy, who in January wrestled their final match before headed to Atlanta. In many ways, one of Paul Heyman's greatest achivements was taking two near unknowns and given them the environment to become something far bigger than the sum of it's parts. Rocco Rock was 42-years-old when he signed with WCW (Grunge, FWIW, was 29), to date neither had done anything of note before the tag team was formed in 1993, and yet through a series of barmy matches and compelling pre-taped segments had got over in front of the Philadelphia crowd. It was the kind of act that nobody would've seen working outside of ECW, and history may well have proven that thought process to be correct.

Departures were now becoming pretty common – Steve Austin's run in ECW, while historically significant, lasted less than four months. Cactus Jack's rumoured departure to the WWF, too, had been bubbling under for what felt like the second half of 1995. ECW's 1996 House Party show in 1996 was setup as a farewell Rock and Grunge, facing off against The Gangstas in a satisfying if predictable main event send off. While a few months prior fans had given Eddie Guerrero and Dean Malenko a send off underscored to "Please don't go", the Enemy received "You'll be back" chants.

The show itself was noteworthy for a few other things. This is the night where Beulah McGillicutty announced her pregnancy, a barmy segment where Raven (who was in theory with Beulah at the time) initially blamed Stevie Richards for the predicament after Beulah revealed the kid wasn’t his, before saying “It’s Tommy’s”. Dreamer came out and the feud that would never end kept on going. Fortunately, while the two were interlinked for much of the year (as was most of ECW's recurring roster) Dreamer and Raven would largely spend the year split apart. While history may suggest that keeping Raven and Dreamer apart was a good thing, you can't help but think ECW could've spiked a lot of curiousity with a proper blow off.

Still, the Enemy departure would be a common theme throughout the year, but at least Paul Heyman was able to keep the ball rolling. Off of the back of a worked shoot in WCW where Brian Pillman walked out on the company in an angle that all bar Eric Bischoff and Kevin Sullivan had no explicit awareness of. Pillman rocked up at ECW's Cyberslam in February, cutting a remarkable promo where he ran down Eric Bischoff, "Bischoff, or should I say, JERK-OFF", called many of ECW's fans "Smart marks" before ending the fascinating ten minute long segment by threatening to whip out his "Johnson" and "piss in this hell-hole". Cap the whole thing off with Shane Douglas storming out and shouting "He's shooting, he's shooting" and you've got yourself one hell of a memorable angle.

The Pillman thing never really went anywhere; save a believe-it-when-you-see-it clip where Pillman wrestled a 6ft tall pencil (in relation to comments by Kevin Sullivan). The Cyberslam show otherwise featured a ridiculous 30 minute match between Sabu and Too Cold Scorpio; a great spectacle topped by Sabu's new "Triple Jump" moonsault where he bounced off the ropes, jumped onto an unfolded chair, onto the top rope before finally launching himself over the guardrial and, in this case, through a vacated table by Too Cold Scorpio. Barmy match, unbelievable spot. This was also the show, really, that started the year plus long feud between Raven and Sandman. While, unquestionably, Raven and Sandman were two of ECW's most popular acts, Sandman was a dreadful wrestler and Raven wasn't that strong either. Focusing the two in the main events (for their "World" title, no less) was perhaps a step too far.

Still, as the months rolled on it was rarely boring in Philadelphia. March bought about a double header of shows in New York and Philadelphia featuring two match of the year candidates on consecutive nights between Rey Mysterio Jr and Juventud Guerrera. In typical ECW booking style each man won a two out of three falls match 2-1, so we'll call it 3-3 over the two nights. While the New York match only aired in bits and pieces on Hardcore TV, the second one got a full airing as both men put on a show of exactly what they were capable of. A very good argument to say this was ECW's best match of 1996.

The shows were noteworthy for a few other things. Namely the debut of Chris Jericho, who went to competitive matches with both Cactus Jack and Taz, New Jack cut a ridiculous promo on night two where he ran down everyone in sight from Eric Bischoff to Vince McMahon in a f-word ladel promo. Cactus Jack also said goodbye to ECW with a match, and a win, over Mikey Whipwreck. Jack, who'd been a really good heel in ECW for much of the previous 7-8 months, made up with many of the ECW crowd before giving credit to the pair of visionaries and creative geniuses without whom ECW wouldn’t exist – he was, of course, talking about Stevie Richards and The Blue Meanie!

In amongst all of this, not-so-quietly going about his business was Taz. Taz had been an act brewing for a while, particularly since the end of 1995 when they’d aligned him with Bill Alfonso. His 1996 will largely be remembered for the feud in the shadows with Sabu, a largely one sided program where Taz would constantly call him out and Sabu would respond by, well, never responding. It made little sense: Sabu wasn’t a character that you ever felt would shirk a fight, nor was it a case of him rarely being there – there were shows where Sabu wrestled where Taz would call him out. Not that ECW was ever a promotion that had particularly defined face and heel lines, but Taz flanked by Alfonso and that fucking whistle was hardly the face, and Sabu could hardly pretend he was the heel given his fan pleasing, death defying style.

Paul Heyman did have a plan for Taz, mind, one that in theory was on the very cutting edge of pop culture and the kind of thing that Heyman and ECW would make their reputation for – although in this case they got it spectacularly wrong. Mixed martial arts had been on the rise for a while, popularised by the often-astonishing success on pay per view of early UFC events that many smaller promotions tried to copy. For a company that had no television exposure, and almost no exposure at all, the fact that they were able to do comparable buyrates on pay per view to even some fairly major wrestling shows from either WCW or the WWF.

The plan ECW had was to try and present Taz as a legitimately tough guy. Taz, in so far, had been presented in a way that made him seem tough – so far so good, but when Joey Styles mentioned the word “shoot-fight” on Hardcore TV it became clear very quickly that the promotion was in over their head. For a start, while we see later in the year that ECW’s fans could absolutely be drawn into believing in something far more than they should, the kind of fan they catered to in the ECW Arena was also the kind of fan that would be able to see through it. Also, and this was something never really addressed, how do you present a show where one match is explicitly “real” and still try and sell the rest of a card without reminding fans that everything else was “fake”.

And it was a question ECW never really got to grips with. They tried the “shoot-fight” thing a few times, with bizarre rules that didn’t really resemble MMA – either modern day or even at the time and action that, in all honesty, didn’t remotely resemble anything that looked like a shoot. It was different to the wrestling on the show, but there’s only so many times you can see a “shoot-fight” where Taz’s opponent goes up for a side suplex. The whole thing crescendoed with Taz facing legit UFC name Paul Varelans – who had a 5-4 MMA record at the time and had fought on four consecutive UFC shows 12 months prior. Varelans was a monster – 6ft 8 and fighting usually at over 300 lbs at a time when UFC didn’t have weight divisions. While his fight technique was absolutely breakable, for a guy of his sheer size and some of the fights he’d had he was quite the get for ECW, looking for both a pay day and a potential opening into pro-wrestling.

I’ve written a full piece on the Varelans ECW run here – but suffice to say it was nearly a disaster. While ECW was a small promotion, Varelans didn’t want a clean loss to Taz to potentially affect his reputation as a fighter. As ridiculous as that might sound it’s possible that people who didn’t know what ECW was might misconstrued it as a real fight, and it’s also possible that he didn’t want to damage his ability to get work in Japan. The match, in that sense, was a disaster – Varelans' demand to be protected meant that the finish involved Perry Saturn coming off the top rope with a dropkick and Taz taking advantage. As Taz took the mic ECW fans drowned him out with “bull-shit” chants to such an extent that Taz had no choice but to agree with them and quickly turn his attention back to Sabu. The angle, which had received a lot of build on television, was quickly dropped and never really mentioned again. It’s not hard to work out why.

ECW, around this time, had essentially moved into a promotion defined by four or five feuds that by and large would sustain themselves for the rest of the year. Raven and Sandman for the ECW title had gotten personal, as Raven had added both Sandman’s ex-wife Lori and Sandman’s child – Tyler – to his group. Sandman, by this time, had Missy Hyatt by his side along with a burgeoning friendship with Too Cold Scorpio to keep him going.

The Raven and Dreamer feud, while rarely far away from the table, had largely subsided. As much as they had storylines that were intertwining, there was only so many times they could do the match, particularly one that Dreamer wasn’t capable of winning. Still, Dreamer had spent months attempting to protect his unborn child, only to find out courtesy of Shane Douglas that the whole pregnancy was a fake. Dreamer, of course, did the only rational thing having spent the better part of three months proclaiming his number one goal was the safety of his girlfriend – he kissed both her and Kimona and acted like the whole thing didn’t matter. While it’s an angle that’s earned a place in ECW folklore, at the time it really didn’t click beyond just being the latest barmy idea of a promotion happy to throw shit at a wall and see if anything stuck.

Dreamer’s focus was largely focussed on “Prime Time” Brian Lee – who you may remember a couple of years prior as the fake Undertaker. As the likes of Mysterio, Juventud and later Chris Jericho departed for WCW it was guys like Lee that Paul Heyman would have to start building around going forward. Good talents but the almost loophole that Heyman was able to exploit when bringing in the likes of Eddie Guerrero, Dean Malenko and Chris Benoit (guys that, legitimately, had claims of being the best wrestler in the world) had firmly slammed shut.

Shane Douglas had been slowly making his way around the block, arriving in an uneasy role of returning hero Douglas slowly pivoted into a genuinely unlikable dick, something exacerbated when Francine turned on the Pitbulls and aligned herself with him. Of course, in the usual ECW style Francine’s turn was done by her pulling up her dress to reveal a pair of knickers emblazoned with “FRANCHISE” written on the back. A barmy match from Heatwave which later included Francine getting superbombed through a table – any thoughts that ECW’s treatment of women might improve in 1996 were very much wide of the mark. As the year would go on, Douglas’ feud with the Pitbulls, including the increasingly improving Pitbull #2 would become one of the best and most heated rivalries in the promotion.

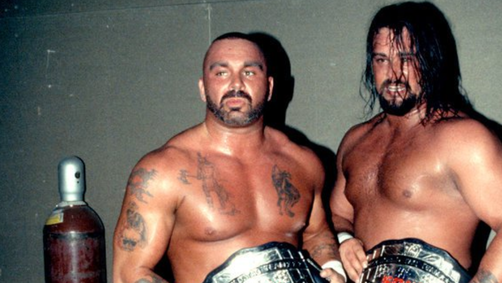

Some other feuds didn’t need much explaining or depth mind. The tag team program with the Gangstas and the Eliminators that essentially went the entire year with very little deviation or evolution simply saw two teams (to quote New Jack) “beat fuck out of each other” in a series of predictably wild and rarely boring tag team matches. I feel like I should devote more time to both teams in a review like this, but it was one of the few things that was predictable about ECW, and while the Gangstas very much played their part it was the all-round emergence of the Eliminators team, punctuated by their head and leg double team “Total Elimination” finisher they were one act that easily stood their ground compared to WCW and the WWF in our end of year awards.

And that’s largely how the promotion rolled throughout the summer. Shows were rarely dull but often failed to hit the storming heights they had at times previously, matches between ECW regulars were good but for once ECW couldn’t hold a torch to what was being put on by WCW. Admittedly, it was largely by a group of Cruiserweights that ECW had once called their own, but for the first time since Paul Heyman took the book there was a good case that ECW wasn’t the hot place in town, at least not for now.

That would be harsh though, many people call 1996 the creative peak of Paul Heyman and in some ways they’re right. While Raven and Sandman often produced dreadful matches (and somehow they actually seemed to get worse) the rivalry between the two was very memorable as Lori Fullington went through a mid-life crisis an while there is a question to be asked at the exploitative nature of using Tyler Fullington in such a role, assuming all parties were in on the situation it added an extra layer to an already very personal feud. Although, and not that it was a great story at the time, the decision later in the year to shoot a crucifixion angle was a step too far, and one that never made it onto Hardcore TV or any video release at the time.

Douglas and the Pitbulls grew very nicely in intensity with an angle where Douglas injured the neck of Pitbull #1. As Douglas bragged and mocked Gary Wolfe for his predicament – Wolfe appeared infrequently wearing a neck halo, initially as a necessity but later retained as a prop. Douglas, finally back to doing what he does best was cutting promos once again with an attitude, showing no mercy what-so-ever that he was with the woman the Pitbull’s used to call theirs. The angle came to a great crescendo in October where, during a heat-filled match between Douglas and Pitbull #2, where Wolfe climbed into the ring, halo and all, before Douglas grabbed by the halo, shook him side to side and dumped him on the mat.

The ringside arena was quickly stormed by wrestlers. In some ways it was a storyline response to Douglas’ actions, but the exodus from the back had another purpose, one that became very, very real. Douglas, as he had been for months, had been drawing heat for months as a dislikeable prick, and a small portion of the ECW fanbase (that really should’ve known better) got wrapped up in the angle so much about three of them vaulted the guardrail. Ringside security mopped them up fairly nicely but if three people wanted the blood of Douglas so much they were willing to get involved then it’s pretty indicative of the general emotion in amongst the audience. Perhaps the strongest visual of the entire year was Douglas being swept away in a sea of ECW talent as they attempted to get him out of harms way to the back. It was easily the strongest angle ECW had put on all year, and indicative of the power of the promotion when they got it right.

Another man that shouldn’t be forgotten in a review of ECW in 1996 is a debuting Rob Van Dam. Van Dam and Sabu had had a great series of matches earlier in the year – although frustratingly the reported best of the three never made it to air. Still after a rivalry that had seen both at each others throats it was a slightly odd decision for Van Dam to ask Sabu to be his tag team partner. But, where it lacked logic it rebounded with a legitimately exciting set of matches with Paul Heyman’s latest imports – the tag team of Dan Kroffat and Doug Furnas.

While the matches usually defied any logic when it came to selling and often when it came to storytelling, the relentless pace and athleticism on show was something to behold. While Van Dam and Sabu undoubtedly bought their talents out of each other as opponents, there’s something to be said for them doing that to an ever greater degree that they perhaps drove each other on as partners. In Kroffat and Furnas, a team that had been around the block in Japan they had a technically excellent opposition that were capable of both offering an alternative to the crazy style and the ability to go along with Sabu and Van Dam’s antics. There were a few contenders in the category, but their tag match that aired at the end of September on Hardcore TV is unquestionably the best match in ECW from 1996 that didn’t involve Rey Mysterio or Juventud Guerrera.

At the November to Remember show a few things became solidified about the current standing and direction of the product. In Stevie Richards, ECW had perhaps the funniest act in wrestling at the time, Richards’ timing and ability to read and react to situations was second to none and, while his parodies alongside the Blue Meanie of things like Baron von Stevie and their famous parody of KISS were all very memorable, with the NWO knock-off “BWO” Richards had found an angle alongside Meanie and Supernova that they’d be able to make money off of decades later. Richards’ comedy timing, made the angle along with the match against Kid Kash (bizarelly named “David Tyler Morton Jericho”) a pleasure to watch as he parodied both Kevin Nash and, with his far superior superkick, Shawn Michaels. His involvement in the show wasn’t limited there, as he took it upon himself to provide commentary over the arena mic for Raven vs Sandman later – it should come as little surprise that it was the best part of the match.

While last year’s November to Remember was perhaps ECW at its peak point (indeed, it won our show of the year) this was perhaps a reflection more of where ECW was. Terry Funk returned in a tag main event that felt far flatter than it should’ve done, save Funk doing a moonsault from the turnbuckle into the crowd. Furnas and Kroffat’s run was so short they’d already joined the WWF by this stage, soon to follow was Too Cold Scorpio, appearing at this show the night before his first live appearance under the gimmick “Flash Funk”. It was also the night that, finally, after a year’s worth of taunting, that Sabu answered Taz’s call. The lights off lights on gimmick enough to tease the pair finally coming together before another lighting flex saw both men disappear into the ether.

It was also this show with the announcement, of sorts, that ECW would be on pay per view in 1997. I say of sorts, the word came from Taz attempting to steal Paul Heyman’s thunder by revealing that he had started signing talent to contracts for a big show in the “first quarter of the New Year”. ECW’s route to pay per view in some ways had come to a head, but in another way it was almost about to fall apart…

At a house show in Revere, Massachusetts on November 23rd 1996 Axl Rotten no showed for a tag match alongside D’von Dudley against the Gangstas. A 17-year-old named Eric Kulas attended the event, lied about his age and his wrestling credentials and managed to convinced those involved to let him replace Rotten. Stories diverage, a little, depending on who you listen to, but it seems like Kulas was willing to “do juice” but didn’t want to do it himself… so he entrusted New Jack. The match wasn’t really much of anything, but when it came time for New Jack to cut open Kulas, he did what (if I was being polite) I’d call a thorough job of it, opening up a serious and deep cut in Kulas’ forhead that caused a serious amount of bleeding that took a long time and a lot of towels to stop. Kulas, mercifully, ended up being ok but it was a story that in all honesty nobody came out of looking good.

It was a sorry incident. A reminder that New Jack’s onscreen character wasn’t really a character at all, a reminder that professional wrestling always was a carny sport – not only did Kulas force his way into a show when he was underage (although, beyond the legalities of it, I’m not sure him being 18 really would’ve changed the story), he also as to be cut as almost a badge of honour, and initiation into a club that he had no right being in. It was also a reminder, as if we needed one, that while ECW was very much a promotion making waves, it was still lightyears behind both WWF and WCW in core competencies.

The sorry, embarrassing incident, also nearly unravelled on ECW’s plans for doing a pay per view. While interviews from Paul Heyman at the time initially said that he’d informed all pay per view providers about it and sent them the tapes – it seems like he was lying. It was less about the incident itself, and more something that fuelled the fire of many people that had never seen ECW before, the perception being that ECW (in many ways correctly) wasn’t like the WWF or WCW, but more in the sense that it wasn’t wrestling at all. Providers were treating ECW like they treated UFC (and some providers were dropping UFC at the time). They thought ECW was UFC, which goes in direct contrast to some people that perceived UFC to be a violent but fake product like ECW. Regardless the incident with New Jack, when it did reach the desks of the relevant people, had opened up a whole new can of worms that ECW had to iron out.

Which, on the cusp of the new year, they did. Just about. Pay per view was a big step forward for ECW, one that would give them the opportunity of creating a major buzz with a live event but also one, theoretically, that would provide them with a significant injection of revenue to enable them to grow. It was perhaps the piece of optimism that the company needed, as they finished 1996 with a roster arguably more average than at any time in the three years prior, yet another main event between Raven and the Sandman (they really were getting worse) and just a promotion that was waiting for something to happen. Fortunately, with pay per view salvaged for early 1997, they had exactly what they needed to aim for.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed