You sometimes have to remind fans that there was a time when there were three pro-wrestling behemoths in North America. Sure, that time was fifty years ago at the time of writing, but while the NWA’s lineage made it to the mid-1990s before dying out, the American Wrestling Association’s identity fell a few critical years sooner. More noteworthy still is that while the AWA closed in 1991, it’s peak really came around a decade earlier, with the advent of Hulkamania.

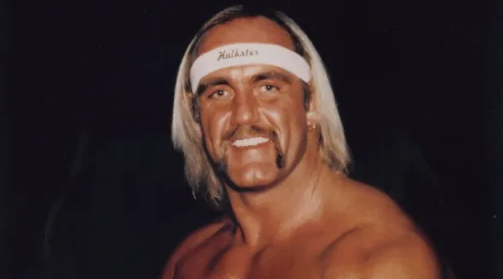

Hulk Hogan’s rise in the AWA was pretty historic, cut by the WWF and then owner Vince McMahon Sr, Hogan was a performer with great size and physique, but one who hadn’t quite cracked “it” yet, whatever “it” was. Hogan’s wrestling success around that time, perplexingly, came more in Japan. Hogan, to his credit, adapted his in-ring style to be more technical than it ever was in North America, and can lay claim to being the only person other than Antonio Inoki to win the original IWGP Heavyweight Title.

But after leaving the WWF, Hogan went off to film a part in Rocky III, before being added to the AWA in 1981. Hogan joined as a heel alongside manager Jimmy Valiant. In those days being a heel meant wearing a sleeveless jacket adorned with the “New York City”, Hogan, even before Hulkamania, realised his selling point was the size of his arms. More pertinently, has he later joked – for some reason he adopted a leg drop as a finisher, rather than some kind lariat that he actually used in Japan. The accumulation of three decades of leg drops would be a big contributing factor to a lot of back surgeries he required later in life.

But, despite a fairly unique promo style – leading with his back towards the camera, a manager and a guy who could claim to be a great mix of New York and California, Hogan’s runs as a heel in the AWA wouldn’t be long for this world. Instead, fans began to rally behind Hogan’s huge frame and a character that started to come to life. Wrestling a much different style to the one he would succeed with in Japan, Hogan perhaps found life easier as a big, stand-up brawler working for a promoter in Verne Gagne that primarily valued work-rate, especially for his major stars.

It was a relationship that would fracture for multiple reasons. Firstly, Hogan’s image boomed following the release of the movie, he capitalised on this by becoming one of the first performers to seriously embrace merchandise as a source of revenue, even if that revenue was direct into Hogan’s pocket. The second challenge was Hogan’s success in Japan – Gagne’s track record for selecting champions was generally a pretty closed book – since 1968 the AWA World Heavyweight Title was only held by Gagne and Nick Bockwinkel, there was no reason to change tact much given that business with both men ran strongly and Bockwinkel wasn’t likely to go anywhere.

This is perhaps why Hogan was never quite the right fit for the AWA. Gagne ran the promotion, but also was a Minnesota native. Bockwinkel, similarly, was born in St Louis. Hogan was a product of Florida, New York and California. Critically too was Hogan being atypical of what Gagne saw in a champion – not just because of the in-ring style but also because Gagne typically ran a heel-led promotion.

But even so, there was a provisional agreement in place to give Hogan the title in 1983. The pair faced off at the Super Sunday card in Minnesota in April 1983 (this is on the WWE Network if you can find it). Hogan won the match clean with the leg drop, only for the result to be thrown out immediately afterwards due to Hogan throwing Bockwinkel over the top rope. At the pace of wrestling in the early-1980s this could’ve been the start of a series of matches that culminated in Hogan finally, properly, winning the belt later in the year.

But it was never to be. Hogan found out while he was touring Japan that Gagne was selling Hogan merchandise and pocketing the proceeds. Gagne’s offer to Hogan would’ve involved Hogan giving up the bulk of his Japanese earnings and his merchandise. Hogan claims to have countered with a 50/50 offer but Gagne declined, leaving thousands of fans in Minnesota feeling short-changed, even if history recognises Hogan as having briefly held the title.

As it was this moment was the beginning for the end of Hogan in the AWA. The iron was still hot but the moment was gone, if Gagne and Hogan couldn’t come to an agreement in the middle of 1983 then little was likely to change in the year that followed. Instead, Hogan returned to the WWF at the beginning of 1984 this time under the leadership of Vince McMahon Jr. By February 1984 Hogan was the WWF Champion and the rest, really, is history. The WWF with Hogan at the helm exploded in the mid-1980s, the AWA lost Hogan as well as a swathe of their well known names like Bobby Heenan, Gene Okerlund, Jesse Ventura and many more.

Bockwinkel, 50-years-old by this point, stayed loyal to Gagne and the AWA but the company was never quite the same again. Despite claiming to be home of many future stars of the industry like Shawn Michaels and Scott Hall in the mid to late 1980s, the AWA, once legitimately one of the “big-three” in professional wrestling eventually closed in 1991.

It’s hard to say how much of a turning point in the industry Hogan not winning the AWA title was. Vince McMahon was expanding regardless, and it’s very plausible that Hogan on top the AWA in 1984 would’ve held Hogan down more than it would have helped the promotion. AWA’s issues that saw so many big departures wouldn’t have likely been solved by Hogan being made the main guy – namely that Gagne (nor anyone) seemed to have the modern vision that Vince Jr had. Still, it’s a fascinating sliding doors moment to think what might have been in the WWF in 1984 had Hogan been carrying the AWA World Title around his waist.

Read More: Why Bobby Heenan and Nick Bockwinkel made the perfect pairing in the AWA

Hulk Hogan’s rise in the AWA was pretty historic, cut by the WWF and then owner Vince McMahon Sr, Hogan was a performer with great size and physique, but one who hadn’t quite cracked “it” yet, whatever “it” was. Hogan’s wrestling success around that time, perplexingly, came more in Japan. Hogan, to his credit, adapted his in-ring style to be more technical than it ever was in North America, and can lay claim to being the only person other than Antonio Inoki to win the original IWGP Heavyweight Title.

But after leaving the WWF, Hogan went off to film a part in Rocky III, before being added to the AWA in 1981. Hogan joined as a heel alongside manager Jimmy Valiant. In those days being a heel meant wearing a sleeveless jacket adorned with the “New York City”, Hogan, even before Hulkamania, realised his selling point was the size of his arms. More pertinently, has he later joked – for some reason he adopted a leg drop as a finisher, rather than some kind lariat that he actually used in Japan. The accumulation of three decades of leg drops would be a big contributing factor to a lot of back surgeries he required later in life.

But, despite a fairly unique promo style – leading with his back towards the camera, a manager and a guy who could claim to be a great mix of New York and California, Hogan’s runs as a heel in the AWA wouldn’t be long for this world. Instead, fans began to rally behind Hogan’s huge frame and a character that started to come to life. Wrestling a much different style to the one he would succeed with in Japan, Hogan perhaps found life easier as a big, stand-up brawler working for a promoter in Verne Gagne that primarily valued work-rate, especially for his major stars.

It was a relationship that would fracture for multiple reasons. Firstly, Hogan’s image boomed following the release of the movie, he capitalised on this by becoming one of the first performers to seriously embrace merchandise as a source of revenue, even if that revenue was direct into Hogan’s pocket. The second challenge was Hogan’s success in Japan – Gagne’s track record for selecting champions was generally a pretty closed book – since 1968 the AWA World Heavyweight Title was only held by Gagne and Nick Bockwinkel, there was no reason to change tact much given that business with both men ran strongly and Bockwinkel wasn’t likely to go anywhere.

This is perhaps why Hogan was never quite the right fit for the AWA. Gagne ran the promotion, but also was a Minnesota native. Bockwinkel, similarly, was born in St Louis. Hogan was a product of Florida, New York and California. Critically too was Hogan being atypical of what Gagne saw in a champion – not just because of the in-ring style but also because Gagne typically ran a heel-led promotion.

But even so, there was a provisional agreement in place to give Hogan the title in 1983. The pair faced off at the Super Sunday card in Minnesota in April 1983 (this is on the WWE Network if you can find it). Hogan won the match clean with the leg drop, only for the result to be thrown out immediately afterwards due to Hogan throwing Bockwinkel over the top rope. At the pace of wrestling in the early-1980s this could’ve been the start of a series of matches that culminated in Hogan finally, properly, winning the belt later in the year.

But it was never to be. Hogan found out while he was touring Japan that Gagne was selling Hogan merchandise and pocketing the proceeds. Gagne’s offer to Hogan would’ve involved Hogan giving up the bulk of his Japanese earnings and his merchandise. Hogan claims to have countered with a 50/50 offer but Gagne declined, leaving thousands of fans in Minnesota feeling short-changed, even if history recognises Hogan as having briefly held the title.

As it was this moment was the beginning for the end of Hogan in the AWA. The iron was still hot but the moment was gone, if Gagne and Hogan couldn’t come to an agreement in the middle of 1983 then little was likely to change in the year that followed. Instead, Hogan returned to the WWF at the beginning of 1984 this time under the leadership of Vince McMahon Jr. By February 1984 Hogan was the WWF Champion and the rest, really, is history. The WWF with Hogan at the helm exploded in the mid-1980s, the AWA lost Hogan as well as a swathe of their well known names like Bobby Heenan, Gene Okerlund, Jesse Ventura and many more.

Bockwinkel, 50-years-old by this point, stayed loyal to Gagne and the AWA but the company was never quite the same again. Despite claiming to be home of many future stars of the industry like Shawn Michaels and Scott Hall in the mid to late 1980s, the AWA, once legitimately one of the “big-three” in professional wrestling eventually closed in 1991.

It’s hard to say how much of a turning point in the industry Hogan not winning the AWA title was. Vince McMahon was expanding regardless, and it’s very plausible that Hogan on top the AWA in 1984 would’ve held Hogan down more than it would have helped the promotion. AWA’s issues that saw so many big departures wouldn’t have likely been solved by Hogan being made the main guy – namely that Gagne (nor anyone) seemed to have the modern vision that Vince Jr had. Still, it’s a fascinating sliding doors moment to think what might have been in the WWF in 1984 had Hogan been carrying the AWA World Title around his waist.

Read More: Why Bobby Heenan and Nick Bockwinkel made the perfect pairing in the AWA

RSS Feed

RSS Feed