Subscribe to the podcast via: iTunes | RSS Feed | Email Newsletter

Popular wisdom says 1995 was the nadir for the WWF, the time in which both the finances and the onscreen product of the company hit rock bottom. The former award likely goes to 1997, the latter is more subjective but could just as easily be applied to 1996. In a company that had struggled with star power ever since Hulk Hogan had left, it seemed like 1995 couldn't beaten in that respect, but 1996 proved that things would certainly get a lot worse before they, mercifully, began to improve.

The year began with hope, with Diesel finally shorn of the WWF title and four men (even if they were all faces) established as the top four guys in the company: champion Bret Hart, Shawn Michaels, Diesel and Undertaker. Added to that was a raft of talent from WCW, funnily enough, headed up by Vader but also including at various points Steve Austin, Brian Pillman, Johnny B Badd (Marc Mero) and Ron Simmons (Farooq). It would be nearly impossible to argue that 1996 wasn't a massive step up in talent on the 12 months prior, but lots of new guys does not an instantly great product make.

And for a while it showed. Vader came in and looked impressive, but after one of the best Raw angles to date where he attacked WWF President Gorilla Monsoon he became increasingly more... average, I suppose you'd say. Shawn Michaels once again stepped up to win the Royal Rumble, and Bret Hart was relegated to playing third wheel in title matches that he was in, where twice in succession interference from either Diesel or Undertaker enabled Bret to retain against the other.

All of this was going on against the undercurrent of a series of angles now known as the “Billionaire Ted” skits. While history remembers them as a couple of angles on Raw the whole series ran from the first show in January right the way through until Wrestlemania, evolving as Vince McMahon’s agenda evolved as he attempted to stop the merger between TBS and Time Warner. It’s too long to explain the whole thing in this piece, but you can read all about it here.

It was in February where the first of the big moves of the year began to unravel. With both Scott Hall and Kevin Nash's contracts expiring at the same time, both were made offers by WCW. Critically, and the tide changed very quickly after this, WCW was offering guaranteed money – which WWF contracts didn't – meaning that both men would be protected from any downswing in business as they no doubt felt (if they didn't help cause) in 1995. Hall has famously said how he asked Vince what it would take to be a main event act, Vince had no answer. He just didn't see it in him. Or, perhaps more specifically, he didn't see it in Razor Ramon.

Hall would end up being suspended for a not-so-coincidental drug testing failure that ruled him out of a match with Goldust at Wrestlemania. His WWF career ended on a flat note with completely unmemorable matches with both The 123 Kid and Vader. Kevin Nash, likewise, would follow suit handing in his notice a couple of weeks later. Both had been offered significant contracts by WCW that the WWF simply had no way of matching. Or, perhaps more the point, having decided Razor had a ceiling and having busted a flush on Nash the year before, neither were top priority. As we'd see later in the year, where it really mattered the company did have an answer.

Still, with Bret having made it through unscathed, barley, after first two pay per views of the year, and Shawn Michaels laying down a marker of excellence for the rest of the year with a match with Owen Hart, the big match was set. Shawn Michaels vs Bret Hart for the WWF Championship at Wrestlemania... in a sixty man Ironman match. The decision was a strange one, to say the least. Sure, in Bret and Shawn they had two of their best in-ring performers to play out a match they'd likely had on the shelf for a while, but there's a very real case their audience just wasn't ready for it.

The build itself was perplexing too. At the end of February the pair had an in-ring showdown where the match and stipulation was made official. With both very much babyfaces, the confrontation was often a flat one where the main subjects of debate surrounded conditioning and admiration of each other as performers. When they met again in the ring ten months later the tone would be very different, but we'll get there!

The match itself essentially engulfed Wrestlemania, running to about 75 minutes total time in a show that clocked in at less than three hours. It was otherwise a completely unmemorable Wrestlemania, save perhaps for a match Undertaker could've easily lost, and the return of the Ultimate Warrior. The main event was good, but predictably overreached in how well the audience would hold it. The decision to have no falls within the regulation time limit was a gamble too far, as was Shawn Michaels inexplicably not attempting his superkick finisher once during normal time, before hitting in twice in the 90 second overtime period. Still, the match was far from a disaster and achieved its main purpose – to get coronate Shawn Michaels at the number one guy and get the title off of Bret Hart so he could take some time off. Read more about my thoughts on the match here.

As for the landscape that Shawn found himself in, he could be forgiven for being a little apprehensive, not that I suspect Shawn Michaels the human being even knew what apprehension was in 1996. With Bret gone and, perhaps more crucially, Hall and Nash on the way out Shawn was not only left with a dearth of opponents but a dearth of allies backstage. Part of the metaphorical strength of the Kliq was the numbers game, with three members of the group leaving Shawn was all of a sudden an island to himself, never mind the fact the list of opponents for him has champion had been decimated.

Still, though, there was no question about it, by April 1996 Shawn Michaels was the guy on top the WWF. The lack of talent and over stars around him meant that all of the WWF eggs were very quickly going to be in the basket of Shawn Michaels. Pay per views for the rest of the year very quickly became games of how much a Shawn main event could save an otherwise dire show, and with Vader not quite being given the treatment he needed there was no natural foe, but if you were willing to look hard enough, there was signs for optimism.

You could trace the stories surrounding Mick Foley's debut in the WWF months before he eventually did, after his heel turn in ECW nothing seemed off limits, including "uncle Eric" - as he spent the last three months of 1995 attempting to convince Tommy Dreamer to move to Atlanta. Still, Foley finished up in Philadelphia in March and debuted on Raw the night after Wrestlemania, under a new gimmick as "Mankind", going straight after the Undertaker.

It's quite hard to work out why the Mankind character was a success, beyond the underlying skills and attitude of the guy playing it. Confusing promos, lullaby entrance music and an initially confusing finisher (that his character quickly explained) which involved sticking two fingers under the tongue of his opponent in a nerve hold. As wrestling edged, kicking and screaming, into a more "shoot" style of character and storyline this new Mankind gimmick felt significantly removed from that. Fortunately, in a potential program with the Undertaker, both men had a found an opponent capable of getting the best out of them.

While Razor Ramon was all but phased out, save a bizarrely even final match with Vader, the WWF had no choice but to keep Diesel in a prominent position with a pay per view to sell. With Diesel now firmly entrenched in a new doesn't-give-a-fuck heel character he was left to a one and done main event with Shawn Michaels. And, as is often the case, with nobody to protect the match ended up being one of the best in the company all year as the pair brawled and fought with weapons including Mad Dog Vachon's prosthetic leg. Both Diesel and Razor were all done on TV, but their run with the WWF wasn’t quite over yet.

It wouldn’t be wrong to say “The Curtain Call” has taken on a life of its own in the twenty years since. The final night of both Hall and Nash in the company in the fabelled MSG setting. After the main event, Nash, Hall, Shawn Michaels and Hunter Hearst Helmsley all got into the ring and embraced before posing in all four corners. It wasn’t really that big of a story at the time – wasn’t even the lead story in the Wrestling Observer that week. While it wouldn’t be incorrect to say the incident did cost Hunter Hearst Helmsley a push, in the short term, you’d need to be looking very closely to notice it – four months earlier he was trading pay per view wins with Duke Droese. Still, given that it took me three months to write, I cover all of it in my 6,000 word piece on the Kliq here.

May also saw the famous “In Your House: Beware of Dog” pay per view, as storms sparked out more than an hour in the middle of the show, people who purchased the show were treated to an hour of almost nothing between the opener and the main event. Mind you, that in itself probably couldn’t be construed to be the worst pay per view of 1996. While the power was out at the building, the show did still go on in near darkness (see the Raw that followed) the “main event” of what would turn out to be night one was a flat encounter between Shawn Michaels and The British Bulldog. Reportedly, neither man found out that the match was even going out live until around half way through. With a superstars taping lined up for the Tuesday they did a make do with the originally aired matches spliced around a live hour for the encore pay per view.

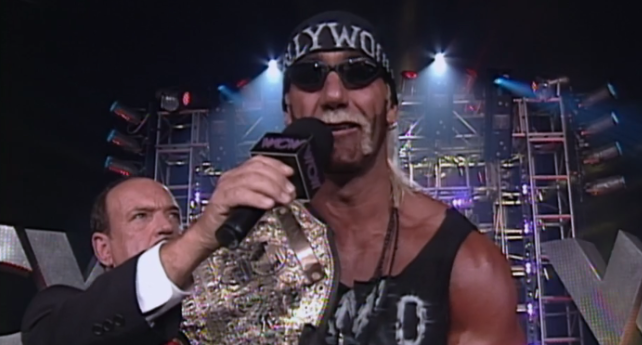

Without wanting to segue too far into WCW territory, it would be folly not to acknowledge Scott Hall’s arrival on Nitro at the end of May. As Nitro moved to two hours Hall just randomly walked out during a match between the Mauler and Mike Enos, of all things. Hall’s promo was the kick-starting of an angle that would quickly spiral into a legal dispute, as lawyer’s in the WWF felt that WCW were trying to present both Hall and later Nash as invaders from the WWF as part of an interpromotional angle – so much so that at June’s WCW pay per view Eric Bischoff literally asked them both if they were “contracted to the WWF”. The legal part of all of this would continue for a long time, and included in the WWF’s issues with the whole thing was them wanting ownership of the Diesel likeness right down to Nash’s goatee beard.

Still, while the company would struggle for about six months to come up with television even 10% as compelling as what was brewing on Nitro, it can’t have been too much of a coincidence that they probably produced their best pay per view since 1994 within weeks of the Outsiders angle starting. With not only Steve Austin winning the tournament (and subsequent promo), but also the first meeting between Mankind and Undertaker being better than most could’ve expected and a main event between Shawn Michaels and the British Bulldog where both men worked hard to make up for their flat match the month before. It would be a while before WWE reached these heights again.

Even with just an hour of Raw to fill every week, Raw sagged – badly. This was a time before main eventers appeared on the show every week, but when Shawn Michaels wasn’t on the show the lack of over talent, to any level, was just startling. Warrior popped a huge rating in April but his ability to draw viewers beyond that seemed more restricted to nostalgia appearances at house shows. And even he ceased to be a playable hand when at the end of June he was suspended following no-showing a string of house shows. Even in 1996, however, the WWE wasn’t above trying to publically expose of its talents, even one as universally supported as Warrior. So at the next available opportunity on Raw they had Gorilla Monsoon calmly announce that Warrior had been suspended and would only be able to return subject to the posting of an appearance bond. Warrior, for now at least, was done.

This left a Warrior shaped hole in the main event of the International Incident pay per view in July. It was a brave move, in itself, to decide to headline a pay per view with a six man tag, condemning viewers to an undercard of scarcely any known talent. A few weeks earlier WCW had promoted a six man main event with Scott Hall and Kevin Nash promising a mystery third partner, it wouldn’t necessarily have been the worst idea for the WWF to have done the same. With the show in Canada, and Bret Hart in theory available, it could’ve been an option. Instead they found a rabbit out of a hat in Psycho Sid.

Sid left the company at the very beginning of the year as a flat heel that, honestly, most people probably didn’t notice had left. He returned in Canada to not only a heroes welcome, but instantly became the most popular member of the roster. The rise to this day still makes no real sense but the WWF suddenly had an asset that in many ways was a far stronger card that the Warrior that he had replaced. With Vader picking up a largely clean pin over Shawn Michaels in the main event, the main event for the summer show was set.

The Summerslam show, it should be said, was a big disappointment. While the feud between Mankind and Undertaker was one of the few redeeming features on the promotion since Wrestlemania, the choice to go with a “Boiler Room Brawl” match – one that took place for about 20 minutes on a video screen – was probably a decision that overreached. With the show only having a small video wall on the stage, the only other way people in person could watch the action was via three TV screens pointing out towards the floor sections of fans. For 90% of the fans in attendance it’s not impossible to think they could barely see the bulk of it before it spilled into ringside.

It was nowhere near the worst thing on the show though, an absolutely dreadful four corners tag match would take that honour. The WWF tag team division had been a disaster for the entire year, the Smoking Gunns just the tip of the talent void that infested the division. The whole card was a disappointment – for those keeping track on Steve Austin following what history says was a career defining promo – he was in the pre-show dark match on this card. Shawn Michaels and Vader was a very good main event, although it was a sign of Vader’s lack of steam that it was no real surprise when he didn’t win the title – despite having won the match twice only for it to be restarted both times. Much like Lex Luger three years prior – he did everything but leave with the title. In many ways, his WWF career from that point on was similarly doomed.

The next couple of months was really focussed around two very different developments off screen. Bret Hart’s contract had technically expired when he left, barring a couple of overseas tour commitments that he had to fulfil. When he finished up a tour of South Africa in September he was free to negotiate, and negotiate he did. Stories at the time varied wildly over exactly what WCW offered Hart, but the contract that would be part-paid by Turner broadcasting would make it the single biggest contract signed by any wrestler who wasn’t named Hulk Hogan. Bret later said it was the kind of deal that he could’ve signed then been sat on a beach three years later.

What’s more is, it was also a deal that was significantly better than anything the WWF could come up with. While WCW’s offer was something in the region of $2-4m per year for three years, the WWF’s deal was a mammoth 20 year contract worth around $14m over the lifetime of the contract, starting out quite high then being scaled back as Bret’s theoretical role would evolve from full timer, to part timer and eventually to someone who worked backstage. The deal, quite frankly, was ridiculous, but it seems like Bret’s main motivation was more to do with being shown what he meant to the company, rather than the size of his actual paycheck. With that in mind, he rejected the offer from WCW and accepted the WWF contract. Funnily enough, his decision would have a big impact on another member of the WWF roster – but more on that in a bit.

The second surrounded Razor Ramon and Diesel. Not actually Scott Hall and Kevin Nash, but the actual characters Razor Ramon and Diesel. In amongst the legal wranglings since Hall and Nash first started appearing on WCW television, Vince McMahon convinced himself that the reason the Diesel and Razor Ramon characters got over on television was more to do with the characterisations themselves as opposed to the two men playing them. Never mind the fact the idea was fucking ludicrous, nor the fact that Nash and Hall as Nash and Hall were already creating far more waves on WCW as themselves as they ever did in the WWF... Vince was convinced, unfortunately.

History might not reflect this, but 1996 was more “shooty” than you might imagine. The Warrior suspension being a good example, Bret’s eventual return being another. The presentation of the new Diesel and new Razor Ramon started life as a series of comments by Jim Ross on commentary saying that he had the scoop on their return. This whole thing underscored by Ross promoting his hotline. The story manifested itself with Gorilla Monsoon explicity mentioning Scott Hall and Kevin Nash by name on Raw, saying neither man had signed a contract with the WWF. With this, the angle pivoted, with Ross saying that he’d never said it was those two men.

It was also, by this stage, that someone backstage twigged this angle wasn’t having the desired effect. The weeks of build we’re all commentary lines and hints that were supposed to build up suspense that Kevin Nash and Scott Hall would somehow reappear on Raw (remember, part of the reason the Outsiders angle was successful in the first place was the idea that Hall and Nash had been sent by the WWF). But if that was the idea it hadn’t turned itself into ratings – Raw continued to sag against Nitro, although one thing never really pointed out about the “Monday Night Wars” was how separate the audiences were. Raw’s numbers often weren’t significantly down on where they were a year or even two years prior, Nitro had just created a (largely) brand new audience of viewers.

Faced with the option of jumping ship completely, they decided to largely continue on as planned, except Ross who was seemingly taking the fall in the angle by being turned heel. The original idea seemed to be that Ross would be the heroic face bringing back two of the promotions most loved characters, as it became clear the reception was going to be less than welcoming Ross was forced to turn heel, with the idea that making false promises was a fuck you to not only the fans but also Vince McMahon. Ross’ shoot promo on Raw was the only highlight of the angle, as he outlines how he was uncerimoniously dumped by the promotion before seemingly accepting responsiblity for the departures of both Nash and Hall. The angle fell off a cliff as Ross introduced the new Razor Ramon, who’s opening monologue was as embarrasing as it was short. It was probably the first and only time that people welcomed the appearance of Savio Vega to cut off the fake Razor before he could say anything worse. Read about the Fake Razor/Diesel angle here.

If there was one thing that was reliable in 1996, however, it was Shawn Michaels. Regardless of the whatever you think of Shawn at this point in time, it was as good as undeniable that he was the best wrestler in North America at this stage; and boy did the WWF need him. While WCW were beginning to settle into a pattern of pay per views where an excellent undercard was followed by a really poor final couple of matches, the WWF had the opposite problem. September’s In Your House: Mind Games being the latest example. The undercard was almost entirely missable, save the tease of an ECW angle with Paul Heyman, Tommy Dreamer and Sandman sitting in the front row; but finished with arguably their match of the year as Shawn Michaels and Mankind wrestled a 25 minute match at a blistering pace. My list of WWF’s best matches of the year is basically a list of Shawn Michaels pay per view matches.

Still, there was one other thing of note on that show – an in ring segment involving Brian Pillman, Owen Hart and Steve Austin. While basic (Austin’s best jibe was basically calling Bret “Shitman”), it was the first real sign that the company were building to a program between Austin and Bret. Which, at the time, was still a bit of a punt, the gap between Bret signing a new deal and him appearing on Raw was pretty short, and it would be over a month after this before he did. With this in mind, they were also giving Austin some stuff to do with him basically feuding with both Mr Perfect and Brian Pillman at the same time. By the end of October Bret was Austin’s only option.

When people talk about signs of revival at the end of 1996 in the WWF, they really do mean the end of 1996. October’s In Your House: Buried Alive was better than many of their recent efforts, but only in the sense it was average rather than really bad. Still, if you’re looking for a historical match-up it does feature Austin and Triple H in the opening match. With Shawn Michaels sitting the event out, the main event lead to the latest brainwave in the Mankind and Undertaker program – a buried alive match. The match was neither great, nor awful, noteworthy most for Mankind doing very little death defying stunts which you’d figure would’ve been a pre-requisite given the name of the match. If Mankind and Undertaker were doing nothing else, they were pushing the boundaries of the otherwise dull as dishwater promotion and getting the best out of each other. We hadn’t spoken about a dreary Undertaker match in months, which was a positive.

Sometime in mid-October Bret Hart finally committed pen to paper on a twenty year contract with the company. Such was the nature of the negotiations there were times when both WCW and the WWF figured they had their man, and times where they were convinced they hadn’t. In rejecting WCW Bret was turning down the chance to be part of an angle that was biblically bigger than anything the WWF were putting out at the time. Maybe that was the problem, the risk of the unknown and the viper’s pit that was the top end of WCW’s roster. As I’ve written here, had Bret have signed for WCW at the time it may have ended the “Monday Night War” before it even really started, such was the ramifications on both sides of his decision.

The biggest victor of Bret’s decision was Steve Austin. While the renewed emphasis on his character in September had seen him pick a fight with seemingly anyone that would listen, by the end of October Brian Pillman would be sidelined for many months with a new injury, and even Mr Perfect (the insurance policy for Austin at Survivor Series if Bret didn’t return) would be unavailable. Funnily enough, he’d left to join WCW in a shock to basically all concerned and, if you’ll pardon the joke setup, it was literally a problem with an insurance policy. Confident of Mr Perfect’s return, it seems like the WWF got involved with his Lloyd’s Of London policy and scuppered a big pay-out that Hennig was due to receive.

Still, Bret vs Austin was on, and it was time to start building to a match people wanted to see. The scene was set, Austin setup at WWF’s studios all the way up North in Connecticut and, much to Austin's chagrin, Bret sat in Calgary on his armchair with his kids at his side. Austin’s change in attitude, even if it was small, didn’t really make sense. Then again, it didn’t really have to. Vince asked Bret some softball questions about ring-rust and Shawn Michaels, Bret – never the best promo, surely couldn’t have been this bad without meaning it, but the stage was set for Austin to retort – Austin tore him apart. It was a landslide. It only lasted a couple of minutes before the segment was wrapped up but Austin had made his point. As they cut away from Bret Austin started mouthing off at a WWF production assistant before throwing him into a nearby ladder. As they cut away from the show Austin left the studio only to be confronted by police arriving. The WWF had finally found some edge in the best and most memorable segment in the three year history of Monday Night Raw. While the former would likely be true for a while yet, the latter would barely last a week.

Along with Bret getting a home visit, earlier in the evening Austin was rather perturbed to find out that WWF camera’s would be making a visit to Brian Pillman’s home the following week. Austin brashly assured Vince McMahon that he too would pay Pillman a visit. And so set in motion what, even over twenty years on, remains one of the most memorable editions of Raw ever. I’ll save you a full rundown (you can read that at length here), but the bizarre mish-mash of a show saw utterly benile wrestling segments split but Austin’s attempts to get into Pillman’s home, while Pillman firstly revealed a 9mm gun before later pulling it on Austin once he eventually made his way inside. The show abruptly cut away... and well... the whole thing was just bizarre. At the end of it, quite what it achieved it’s not even easy to say.

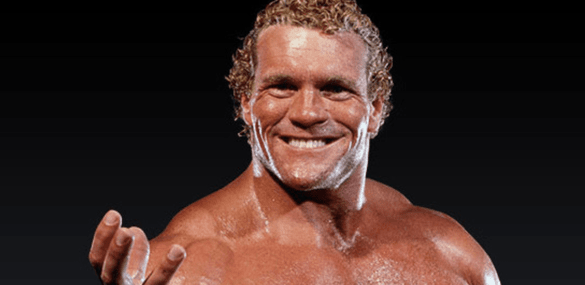

Still, it setup Survivor Series which, amongst other things, saw the debut of Rocky Maivia, the sole survivor having beaten such luminaries as Goldust and Crush from a 2 on 1 disadvantage. The show also debuted a vanilla looking tag team of Doug Furnas and Phil Lafon, a team that up until about three months previously had plied their trade almost exclusively in Japan, including Dave Meltzer awarding them a five star match in 1992. For once, it felt like the WWF had beaten WCW to the punch when it came to a major signing in 1996, although it never turned out that way. Still, their showing in the opener was very, very good. Just a shame nobody ever bothered to come up with any sort of character.

The two big matches on the show delivered about as well as anybody could've expected. Steve Austin vs Bret Hart, while I think can be overrated, is a match that is wonderfully economical and achieved exactly what it set out to achieve. Bret, in his first match on North American soil since facing Michaels in March, worked a methodical style with very few big spots that managed to get Austin over as a credible challenger at that level. Still, Bret retained thanks to pinning Austin while in a submission. The best, though, was yet to come.

Sid vs Shawn Michaels had no right to be any good. As the two men made their entrances it was pretty clear Madison Square Garden had a mixed view of Michaels, by the end it was anything but. Sid walked in the theoretical heel, and left with the title and the support of the majority of the crowd. More surprising still was just how good the match was, a motivated Sid just able to hang with Shawn enough where the match actually threatened to be very good. A fucked finish involving Sid hitting with Jose Lothario with a camera, then Shawn before powerbombing him. The whole thing was convoluted, never mind Lothario looking like he was having a heart attack (which, made no difference to how the angle was going to get over) and nobody coming to tend to him for about five minutes. Still, we had a new Champion. This Survivor Series, like the last Survivor Series, like the Survivor Series before that.

Seemingly it was now time for the annual changing of the guard at the top. Sid a puzzling choice, but one that Vince McMahon took as he needed a bit of a fresh act at the top, and there was a very strong argument that Sid was the strongest babyface the company had at the time (well, so strong in fact they basically turned him heel). Still, hot on the heels of Steve Austin's attitude change they apparently wanted an excuse for Shawn to do the same thing. Two weeks later they had Shawn appearing at the home of Jose Lothario, the satellite interview started out quite normally before Michaels slowly began to lose his shit. "No more Mr Nice Guy" indeed. Still, as the company had booked out the 70,000 seat Alamodome in San Antonio for the Royal Rumble then they had to get something moving. And, despite Sid's first title defence being againt Bret Hart in December, all signs pointed towards Michaels seeking revenge (not only for his title, but also the weary Lothario) in January, with Bret winning the Rumble and setting up a Wrestlemania rematch.

There was time for a late entry into the worst pay per view of 1996, with In Your House: It's Time (a show that didn't include Vader), featuring a series of phoned in matches, a non-sensical Armageddeon Rules match and a main event between Bret Hart and Sid that was almost painfully bad. Filler was the name, but clearly something had changed. The next night on Raw opened with a heel vs heel match between Vader and Steve Austin, saw Jerry Lawler ask Goldust if he was “well, you know… queer?” and finished with a reprise of the Shawn Michaels collapse angle thirteen months earlier, except rather than using Shawn Michaels they used Billy Gunn. We had just enough time left in the year for a Bret and Shawn show-down that was almost a 180 on their February confrontation. Bret called out Shawn for appearing in Playgirl (“girls don’t read that, you know”) before Shawn basically said that Bret sleeps around on the road. Dragged kicking and screaming they may be, the WWF was about to become a very different place in 1997.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed